Is a Transition Beyond Consumer Society a Realistic Prospect?

Maurie J. Cohen,

Professor of Sustainability Studies and Chair of the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the New Jersey Institute of Technology.

- Introduction

This chapter considers a growing pattern of speculation over the past two decades about the pending end of consumer society as a predominant mode of social and economic organization. While such conjecture has long been a staple of certain modes of eco-catastrophic and related modes of thought, it began to assume greater prevalence at the start of the new millennium (Ekins 1998; Schwarz and Schwarz 1999; Kaza 2000; Scott 2001; Trentmann 2004; Princen 2005; c.f. Stiglitz 2008). The 2007 financial collapse ‒ which exposed in especially graphic form the fragility of the international banking system and the fecklessness of its most prominent institutions ‒ gave this work newfound relevance (Benett and O’Reilly 2009; Frank 2009; Hamilton 2009; Perez and Esposito 2010; Etzioni 2011). Also important have been supplementary modes of thinking that have considered the failing imagination and adaptability of mainstream media and marketing industries (Lewis 2013), new forms of hedonism (Soper 2013), and several so-called “headwinds” due to demographic contraction, income inequality, and slowdown in productivity improvements (Heinberg 2011; Galbraith 2014; Gordon 2017; King 2018). Other scholars have ventured ambitious views and sweeping assessments of pending futures both as a result of evolving processes of social change (Silla 2017, Vänskä 2018; c.f. Pérez and Esposito 2010) and disruptive economic and environmental upheavals (Campbell et al 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic provided a new and mostly unanticipated jolt to this speculation as governments implemented lock-downs, workers vacated central cities, and shoppers abandoned their customary practices (Cohen 2020, Goffman 2020; Wells 2020; Bodenheimer and Leidenberger 2020).

This series of recent disruptions has generated a modest literature focused on the related themes of “post-consumerism,” “beyond consumerism,” and “end of consumer society.” Authors variously suggest that it is not unreasonable to anticipate a transformation of historic proportions where frantic shopping and consumption-fueled status acquisition fades away and are replaced by new practices and aspirations (Varey and McKie 2010; Cohen 2013; 2015a, 2015b; Cohen et al 2017; Blühdorn 2017).[1] Importantly, and perhaps unsurprisingly, there is quite a bit of divergence ‒ and indeed polarization ‒ on the basic contours of the era that might replace consumer society. Some commentators foresee a dystopic future characterized by multitudes of economically precarious neo-peasants and depleted natural environments (Standing 2011; Wallace-Wells 2019; McKibben 2019) while others offer more optimistic portrayals premised on, for instance, a digitally-driven leisure society (Rifkin 1995; Ferris 2009; Srnicek and Williams 2015).

This chapter traces out several of the main features of an anticipated transition beyond consumerism. The next section situates the discussion within the context of the familiar Stages of Economic Growth model originally introduced in the 1960s by the American economist, political theorist, and presidential advisor W. W. Rostow. The third section highlights how demographic contraction in most affluent countries will make it more difficult to achieve requisite annual increments of economic growth and this situation will lead to the active implementation of new metrics that supplant GDP. The chapter concludes with a few brief comments about the importance of governance in an eventual transition.

- The Rise of Consumer Society

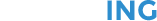

One does not need to be a strict adherent of Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth model to accept its basic premise that societal development in many countries over the past approximately 200 years has tended to follow a broadly generic pattern of modernization (Rostow 1960; see also Rist 1997) (see Figure 1). Despite its neo-colonial conceptual underpinnings, the approach continues to attract considerable contemporary attention on the part of mainstream institutions and policy makers more than a half century after its initial formulation (see, e.g., Costa and Kehoe 2016). Starting from a baseline condition of “traditional society,” countries are envisioned to proceed to the “pre-take-off” stage and then to the “take-off” stage. Stability is achieved during the “maturity” stage and the process culminates with the “high-mass consumption” stage. To be sure, some nations have moved more steadily through the various phases and others more sluggishly; there are even indications of cases ‒ Pakistan is a prominent example ‒ of societies stalling out at a mid-stage of the progression. Further, there are instances that suggest it is possible under certain propitious circumstances to leapfrog particular stages of the sequential process (Soete 1985; Steinmueller 2001). The immediate point, however, centers on Rostow’s contention that the end-state of the linear evolution is achievement of a “high mass consumption” society.[2]

Figure 1: Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth Model

(Source: https://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/newsletterarticles/utopia-and-economic-development/)

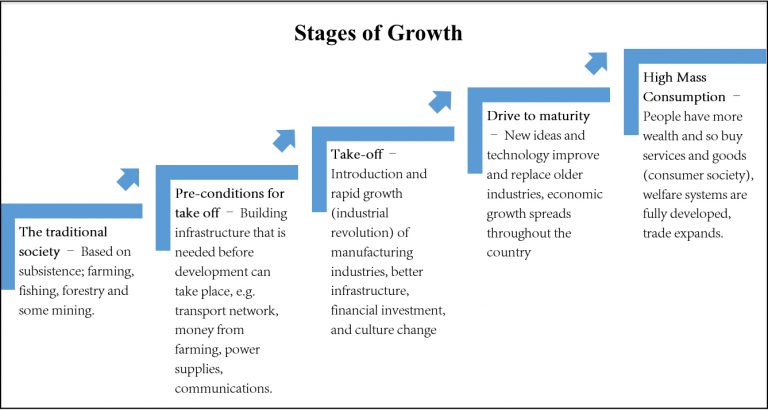

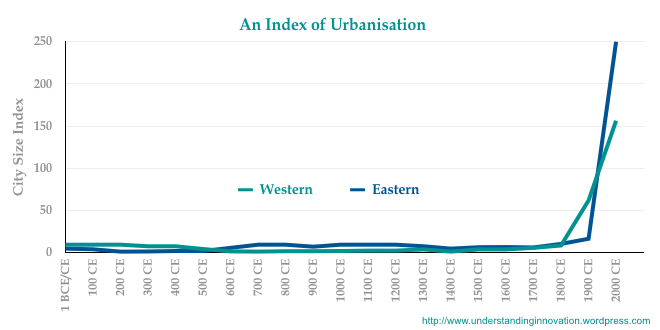

What is for current purposes especially pertinent about Rostow’s model is that the “developmental” process terminates with the high-mass consumption phase.[3] The framework does not consider what might happen when the structural underpinnings of this stage began to erode and what might supplant consumption as the organizational logic under such conditions (see Soper 2017; Trebeck and Williams 2019). While Rostow may have regarded mass consumption as the zenith of human civilization, other modernization theorists have long anticipated industrial revolutions that would supplant prevalent forms of consumerism (Bell 1976; Toffler 1980; see also Harrison 2016). Especially notable in this regard are the so-called “long-wave theories” of Nikolai Kondratieff (2010 [1935]) and Joseph Schumpeter (1994 [1942]) that posit the unfolding of sequential upsurges and downfalls of technologically driven development (see Figure 2). These conceptions have contributed to various expressions of techno-utopianism of which the most familiar manifestation today is Industry 4.0 that anticipates a future propelled by artificial intelligence, intelligent manufacturing and cyber-physical innovations (Schwab 2017) (see figure 3). Popularized by the World Economic Forum, the proposition is that we are on the verge of a massive wave of technoscientific change driven by advanced robotics, big data analytics, 3-D printing, the Internet of things, and more.

Figure 2: Schumpeterian Waves

(Source: https://understandinginnovation.blog/2016/09/13/cities-companies-and-innovation-accelerate/)

Figure 3: Timeline from Industry 1.0 to Industry 4.0

(Source: https://www.edn.com/industry-4-0-is-closer-than-you-think/)

It merits stressing here that a high-mass consumption society is not, as implied by Rostow, the inevitable endpoint of a developmental process. More specifically, the entrenchment of consumerism is attributable to massive assistance the part of policy makers, economic planners, and numerous others beginning in the early decades of the twentieth century. In the first instance, specific strategies were implemented to shift long-standing and deeply engrained propensities of would-be consumers to save surplus income rather than spend it on what in prior times were regarded as mostly superfluous goods. In other words, a prerequisite of consumerist lifestyles was the establishment and diffusion of a more present-oriented mindset. This shift entailed the implementation of publicly provided systems of social security, the assurance of a living wage for most workers, and the encouragement of lenient lending standards by financial institutions (Glickman 1997; Hayden 2002; Cohen 2003; De Grazia 2006; Hyman 2012; Cogan 2017). In addition, a consumer society rests on interdependent infrastructural and provisioning systems for housing, transportation, agriculture, and so forth to ensure cost-effective production and delivery over long distances (Lewis 1997; Rubenstein 2001; see also Petroski 2016). In addition, consumerism requires communications networks that allow ‒ and indeed encourage ‒ the permissive dissemination of promotional inducements to enliven and maintain demand (Jacobson and Mazur 1995; Schor 2004). And schools and other educational facilities need to adapt their curricula to emphasize instructional content that stimulates among students a desire to consume both presently and in the future (Molnar 1996; Spring 2003; Lin 2004).

To put these factors into a historical context, the contemporary consumer society ‒ at least the vanguard manifestation of it that exists in the United States ‒ arose from many of the same factors that gave rise to the Roosevelt-era New Deal. Chief among these catalysts was the need to incentivize consumers to absorb the surplus output of increasingly productive manufacturers and farms and to avoid the over-accumulation crisis that contributed to the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 (Douglas 1934; Jacobs 1999; Robbins 2017). Many of these same policies were then amplified following World War II to ensure stable and vigorous demand for houses, automobiles, and other durable consumer goods (Walker 2012; see also Harvey 2012).[4]

While there has been variation across different countries, a unified storyline has in recent decades persisted across virtually all countries of the global North in which economics, politics, and policy making have been impelled by an expansionary logic. Central to this logic has been the expectation that population, affluence, energy use, and material consumption, would continue to increase into the indefinite future (Collins 2000; Schmelzer 2016). It was generally acknowledged that recessions of differing lengths of time were unavoidable but the general expectation was that economic growth was the accelerant of human well-being. Sustainability scientists, historians, and others have described this period as the “Great Acceleration” and have documented its implications across a wide range of material flows (Steffen et al 2007; McNeill and Engelke 2014).

- Anticipating a Future Beyond Consumer Society

Over the past approximately thirty years, new sensibilities have gradually begun to creep in and it is no longer heretical to speculate about the demise of consumer society. Separate from ‒ but in some cases in reaction to ‒ there are today numerous examples from around the world of people turning away from consumerist lifestyles and challenging long-standing commitments predicated on the idea that a good life is effectively achieved through material accumulation. Some lapsed consumers are joining communal networks that encourage participants to share a diverse range of products rather than purchase their own (Sekulova et al 2013; Schor 2010; Cohen 2017). Oher putative post-consumers are purposefully downshifting by cutting back on working hours while making proportionate reductions in consumption (Alexander and Ussher 2012; Kennedy et al 2013; but see also Lindsay at al 2020 and Antal 2020).

These defiant efforts are notable and represent what transitions researchers refer to as “niche-based” innovations (Cohen et al 2013; Geels et al 2015; Greene 2018; Welch and Southerton 2019). However, it requires ambitious vision ‒ and a big leap of faith ‒ to envisage how they might scale up and become more than interesting countercultural social experiments.[5] Not infrequently, these initiatives encounter indifference, but they can also become targets for vociferous opposition because they fly forcefully in the face of existing societal arrangements and raise difficult questions about the efficacy of the prevailing political and macroeconomic order (see, for example, Kaufman 2009; Berry and Portney 2017).

Whole counties, regardless of the underlying reasons, can also find themselves impugned for diverting from the customary expansionary path. Especially notable in this regard is Japan which despite having the third largest economy in the world as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), has consistently struggled over the past three decades to meet standard growth expectations for affluent nations (Berman 2015; Pilling 2018; see also Klien 2016). The reasons for the country’s negligible rates of economic growth are complicated but the situation stems in large part from low fertility and demographic aging. Since the collapse of its widely celebrated “bubble economy” of the late 1980s, Japan has been trapped in a mostly unremitting process of contraction that has extended from the “lost decade” of the 1990s to the “lost decades” of the 2000s and 2010s (Fletcher and von Staden 2014; Funabashi and Kushner 2015). Most policy efforts to reverse this pattern ‒ for instance by incentivizing families to increase reproduction ‒ have failed to achieve their objectives.

Japan, however, is not alone and across large parts of Asia (Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore) extremely low fertility rates have become normalized and ‒ unless there is a highly unlikely reversal ‒ these nations will continue to follow in the path of their regional neighbor (Eggleston and Tuljapurkar 2011; Suzuki 2013; Pesek 2014). Recent demographic evidence from China suggests that even in the world’s most populous country, the future is apt to entail demographic (and economic) shrinkage in future decades. This is realization of the long-anticipated problem whereby the country is not able to become rich before it gets old (England 2005; Eberstadt and Verdery 2021)

Demographic contraction is by no means an exclusively Asian phenomenon. Most of Europe and North America is following a similar trajectory and absent significant changes in immigration policy will find themselves with smaller populations by the middle of the current century (Last 2013; Cohen 2016; Douglas 2020). It becomes extremely difficult, as the forerunner case of Japan demonstrates, to maintain positive rates of economic growth when population is shrinking.

As it becomes more challenging for countries of the global North to achieve satisfactory rates of consumer-driven economic growth, the extant circumstances will become discomfiting and will eventually become politically necessary to find new measures with which to demonstrate achievement. This pressure will be even more intense if nations such as Bangladesh, Egypt, and Vietnam continue to lead the international competition as they did in 2020.[6] It is thus likely that governments of already affluent nations will need to deploy a new yardstick with which to demonstrate distinction. This situation brings to mind the economist Milton Friedman’s famous dictum that “Only a crisis ‒ actual or perceived ‒ produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.”

There is currently no shortage of alternatives “laying around.” Over the past three decades, economists and others have formulated novel measures that do not merely measure the aggregate size of a country’s output, but that rather focus on criteria that are more meaningful and important for enhancing credible conceptions of well-being (Fioramonti 2013; Lepenies 2016). Already familiar alternatives include the human development index (HDI), the index of healthy life expectancy (HLE), the genuine progress indicator (GPI), and index of sustainable economic welfare (ISEW) (Stockhammer et al 1997; Bleys 2012; Giannetti et al 2015). Interestingly (and probably a precursor of what is to come), several countries have already begun to calculate and publicize their performance on these alternative measures. Probably most famous is case of Bhutan that has long relied on its National Happiness Index (NHI) to assess societal progress (Bok 2013; Hayden 2015). In 2010, the French government sponsored a commission led by Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi that produced a report entitled Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up that received a great deal of international attention (Stiglitz et al 2010; see also Thomas and Evans 2010 and Bijl 2011). The same year, the UK Office for National Statistics launched its Measuring National Wellbeing Programme and the results of an annual survey are published on an online dashboard and distributed through other means (Hicks et al 2013; Everett 2015). In 2019, the government of New Zealand began to use a wellbeing measure to set its national budget priorities (Roy 2019; Charlton 2019).

This is only a partial list of initiatives that have started to sideline GDP as the primary headline indicator of national progress and it seems inevitable that more governments across the global North will take similar action as they continue to encounter difficulty delivering on customary notions of success. In an effort to demonstrate that they “can get the job done” the goalposts will shift and new indices will gain greater prominence, over time supplanting GDP from its preeminent position.

Once the focus for evaluating the achievements of political parties becomes oriented less around impelling consumer-driven economic growth and more toward robust and effectual measures of well-being, we will likely start to see the withering of consumer society. This mode of socioeconomic organization will not be able to survive without the pump-priming public investments, enabling policy inducements, and tireless boosterism that governments have regularly been able to confer.

- Conclusion

The foregoing discussion arguably helps to provide some insights into how consumerist lifestyles could recede but questions remain about what will follow. It remains difficult to discern whether the eventual demise of consumer society will give rise to a successor that privileges solidarity, equity, and inclusivity as opposed to disharmony, inequality and exclusivity. Much will depend on how we govern a transition beyond consumerist lifestyles and the choices we make along the way.[7] This will mean purposeful planning of social change and dispensing with outmoded doctrines that have long ceased to provide useful guidance. We will likely need to develop new frameworks and vocabularies for talking about sufficiency, planetary boundaries, and societal obligations in novel and innovative ways.

References

Alexander, S. and S. Ussher. 2012. The voluntary simplicity movement: a multi-national survey analysis in theoretical context. Journal of Consumer Culture 12(1):66‒86.

Antal, M., B. Plank, J. Mokos, and D. Wiedenhofer. 2020. Is working less really good for the environment? A systematic review of the empirical evidence for resource use, greenhouse gas emissions and the ecological footprint. Environmental Research Letters 16(1): 013002.

Bell, D. 1976. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting. New York: Basic Books.

Benett, A. and A. O’Reilly. 2010. The end of hyperconsumerism. The Atlantic, 28 July (https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2010/07/the-end-of-hyperconsumerism/60558/).

Bengtsson, M., E. Alfredsson, M. Cohen, S. Lorek, and P. Schroeder. 2018. Transforming systems of consumption and production for achieving the sustainable development goals: moving beyond efficiency. Sustainability Science 16(6):1533‒1547.

Berman, M. 2015. Neurotic Beauty: An Outside Looks at Japan. Portland, OR: Water Street Press.

Berry, J. and K. Portney. 2107. The Tea Party versus Agenda 21: local groups and sustainability policies in U.S. cities. Environmental Politics 26(1):118‒137.

Bijl, R. 2011. Never waste a good crisis: towards social sustainable development. Social Indicators Research 102(1):167‒168.

Bleys, B. 2012. Beyond GDP: classifying alternative measures for progress. Social Indicators Research 100(3):355‒376.

Blühdorn, I. 2017. Post-capitalism, post-growth, post-consumerism? Eco-political hopes beyond sustainability. Global Discourse 7(1):42‒61.

Bodenheimer, M. and Leidenberger 2020. COVID-19 as a window of opportunity for sustainability transitions? Narratives and communication strategies beyond the pandemic. Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 16(1):61‒66.

Bok, D. 2010. The Politics of Happiness: What Governments Can Learn from the New Research on Well-Being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Campbell, N., G. Sinclair, and S. Browne. 2019. Preparing for a world without markets; legitimising strategies of preppers. Journal of Marketing Management 35(9‒10): 798‒817.

Charlton, E. 2019. New Zealand has unveiled its first “well-being” budget. World Economic Forum, May 30 (https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/05/new-zealand-is-publishing-its-first-well-being-budget/).

Cogan, J. 2017. The High Cost of Good Intentions: A History of U.S. Federal Entitlement Programs. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Cohen, L. 2003. A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. New York: Knopf.

Cohen, M. 2013. Collective dissonance and the transition to post-consumerism. Futures 52: 42‒51.

Cohen, M. 2015a. Toward a post-consumerist future? Social innovation in an era of fading economic growth, pp. 426‒439 in L. Reisch and J. Thøgersen, Eds., Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Cohen, M. 2015b. The decline and fall of consumer society? Implications for theories of modernization, pp. 33‒40 in A. Martinelli and C. He, Eds., Global Modernization Review: New Discoveries and Theories Revisited. Beijing: World Scientific Publishing.

Cohen, M. 2016. Demographic contraction and sustainable consumption in high-consuming countries: an assessment of OECD members. Unpublished paper available from author.

Cohen, M. 2020. Does the COVID-19 outbreak mark the onset of a sustainable consumption transition? Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 16(1):1‒3.

Cohen, M., H. Brown, and P. Vergragt, Eds. 2013. Innovations in Sustainable Consumption: New Economics, Socio-technical Transitions and Social Practices. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Cohen, M., H. Brown, and P. Vergragt, Eds. 2017. Social Change and the Coming of Post-Consumer Society: Theoretical Advances and Policy Implications. London: Routledge.

Collins, R. 2000. More: The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Costa, D. and T. Keohoe. 2016. A general framework and taking off into growth. Economic Policy Paper 16-5. Minneapolis: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (https://www.minneapolisfed.org/~/media/files/pubs/eppapers/16-5/epp-16-5-stages-of-economic-growth-revisted-part1).

De Grazia, V. 2006. Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance through Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Douglas, C., Ed. 2020. Barren States: The Population Implosion in Europe. New York: Bloomsbury.

Douglas, P. 1934. The role of the consumer in the New Deal. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 172(1):98‒106.

Eberstadt, N. and A. Verdery. 2021. China’s shrinking families: the demographic trend that could curtail Beijing’s ambitions. Foreign Affairs, April 7.

Eggleston, K. and S. Tuljapurkar. 2011. Aging Asia: The Economic and Social Impactions of Rapid Demographic Change in China, Japan, and South Korea. Palo Alto, CA: Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center.

Ekins, P. 1998. Can humanity go beyond consumerism? Development 41(1):23‒27.

England, R. 2005. Aging China: The Demographic Challenge to China’s Economic Prospects. Westport, CT: Praeger Press.

Etzioni, A. 2004. The post affluent society. Review of Social Economy 62(3): 407‒420.

Etzioni, A. 2011. The new normal. Sociological Forum 26(4): 779‒789.

Everett, G. 2015. Measuring national well-being: a UK perspective. Review of Income and Wealth 61(1):34‒42.

Ferriss, T. 2009. The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9‒5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich, Revised Edition. New York: Harmony.

Fioramonti, L. 2013. Gross Domestic Problem: The Politics Behind the World’s Most Powerful Number. London: Zed Books.

Fletcher, W. and P. von Staden, Eds. 2014. Japan’s “Lost Decade”: Causes, Legacies and Issues of Transformative Change. London: Routledge.

Frank, R. 2009. Post-consumer prosperity. The American Prospect 20(3): 12‒15.

Fuchs, D. and S. Lorek. 2005. Sustainable consumption governance: a history of promises and failures. Journal of Consumer Policy 28(3):261‒288.

Fukuyama, F. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press.

Funabashi, Y. and B. Kushner, Eds. 2015. Examining Japan’s Lost Decades. London: Routledge.

Galbraith, J. 2014. The End of Normal: The Great Crisis and the Future of Growth. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Geels, F., A. McMeekin, J. Mylan, and D. Southerton. 2015. A critical appraisal of sustainable consumption and production research: the reformist, revolutionary, and reconfiguration positions. Global Environmental Change 34:1‒12.

Giannetti, B., F. Agostinho, C. Almeida, D. Huisingh. 2015. A review of limitations of GDP and alternative indices to monitor human wellbeing and to manage eco-system functionality. Journal of Cleaner Production 87(1):11‒25.

Gilman, N. 2004. Mandarins of the Future: Modernization Theory in Cold War America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Glickman, L. 1997. A Living Wage: American Workers and the Making of Consumer Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Goffman, E. 2020. In the wake of COVID-19, is glocalization our sustainability future? Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 16(1):48‒52.

Gordon, R. 2017. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Greene, M. 2018. Socio-technical transitions and dynamics in everyday consumption practices. Global Environmental Change 52:1‒9.

Hamilton, C. 2009. Consumerism, self-creation and prospects for a new ecological consciousness. Journal of Cleaner Production18(6):571‒575.

Harrison, D. 2016. The Sociology of Modernization and Development. London: Routledge.

Harvey, M. 2012. The environmental history of the Truman years, 1945‒53, pp. 260‒286 in D. Margolies, Ed., A Companion to Harry S. Truman. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hayden, A. 2015. Bhutan: blazing a trail to a postgrowth future? Or stepping on the treadmill of production. Journal of Environment and Development 24(2):161‒184.

Hayden, D. 2002. Redesigning the American Dream: The Future of Housing, Work, and Family Life. New York: W. W. Norton.

Heinberg, R. 2011. The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society.

Hicks, S., L. Tinkler, and P. Allin. 2013. Measuring subjective well-being and its potential role in policy: perspectives from the UK Office for National Statistics. Social Indicators Research 114(1):73‒86.

Hyman, L. 2012. The politics of consumer debt: U.S. state policy and the rise of investment in consumer credit, 1920‒2008. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 644(1):40‒49.

Inglehart, R. 1977. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ivanova, M. 2011. Consumerism and the crisis: wither “the American dream?” Critical Sociology 37(3): 329‒350.

Jacobs, M. 1999. “Democracy’s third estate”: New Deal politics and the construction of a consuming public. International Labor and Working Class History 55:27‒51.

Jacobson, M. and L. Mazur. 1995. Marketing Madness: A Survival Guide for a Consumer Society. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Kaufman, L. 2009. A cautionary video about America’s ‘stuff.’ The New York Times, May 10 (https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/11/education/11stuff.html).

Kaza, S. 2000. Overcoming the grip of consumerism. Buddhist-Christian Studies 20:23‒42.

Keller, M., B. Halkier, and T.-A. Wilska. 2016. Policy and governance for sustainable consumption at the crossroads of theories and concepts. Environmental Policy and Governance 26(2):75‒88.

Kennedy, E., H. Krahn, and N. Krogman. 2013. Downshifting: an exploration of motivations, quality of life, and environmental practices. Sociological Forum 28(4):764‒783

King, S. 2018. When the Money Runs Out: The End of Western Affluence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Klien, S. 2016. Reinventing Ishinomaki, reinventing Japan? Creative networks, alternative lifestyles and the search for quality of life in post-growth Japan. Japanese Studies 36(1):39‒60.

Kondratieff, N. 2010 [1935]. The Long Waves in Economic Life. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing.

Last, J. 2013. What to Expect When No One’s Expecting: America’s Coming Demographic Disaster. New York Encounter Books.

Lepenies, P. 2016. The Power of a Single Number: A Political History of GDP. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lewis, J. 2013. Beyond Consumer Capitalism: Media and the Limits to Imagination. Cambridge: Polity.

Lewis, T. 1997. Divided Highways: Building the Interstate Highways, Transforming American Life. New York: Viking.

Lin, S. 2004. Consuming Kids: The Hostile Takeover of Childhood. New York: New Press.

Lindsay, J., R. Lane, and K. Humphery. 2020. Everyday life after downshifting: consumption, thrift, and inequality. Geographical Research 58(3):275‒288.

Mackinnon, J. 2021. The Day the World Stopped Shopping. New York: HarperCollins.

McKibben, B. 2019. Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? New York: Henry Holt and Company.

McNeill, J. and P. Engelke. 2014. The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene Since 1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Molnar, A. 1996. Giving Kids the Business: The Commercialization of America’s Schools. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

O’Rourke, D. and N. Lollo. 2015. Transforming consumption: from decoupling to behavior change, to systems changes for sustainable consumption. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 40:233‒259.

Perez, F. and L. Esposito. 2010. The global addiction and human rights: insatiable consumerism, neoliberalism, and harm reduction. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 9 (1‒2):84‒100.

Pesek, W. 2014. Japanization: What the World Can Learn From Japan’s Lost Decades. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Petroski, H. 2016. The Road Taken: The History and Future of America’s Infrastructure. New York: Bloomsbury.

Pilling, D. 2018. The Growth Illusion: Wealth, Poverty, and the Well-being of Nations. New York: Duggan Books.

Princen, T. 2005. The Logic of Sufficiency. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rifkin, J. 1995. The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era.

Rist, G. 1997. The History of Development: From Western Origins to Global Faith. London: Zed Books.

Robbins, M. 2017. Middle Class Union: Organizing the “Consuming Public” in Post-World War War I America. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Rostow, W. 1960. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roy, E. 2019. New Zealand’s world-first “wellbeing” budget to focus on poverty and mental health. The Guardian, May 14 (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/14/new-zealands-world-first-wellbeing-budget-to-focus-on-poverty-and-mental-health).

Rubenstein, J. 2001. Making and Selling Cars: Innovation and Change in the U.S. Automotive Industry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Schmelzer, M. 2016. The Hegemony of Growth: The OECD and the Making of the Economic Growth Paradigm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schor, J. 2004. Born to Buy: The Commercialized Child and the New Consumer Culture. New York: Scribner.

Schor, J. 2010. Plenitude: The New Economics of True Wealth. New York: Penguin.

Schumpeter, J. 1994 [1942]. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London: Routledge.

Schwab, K. 2017. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Geneva: World Economic Form.

Schwarz, W. and D. Schwarz. 1999. Living Lightly: Travels in Post-Consumer Society. Charlbury: Jon Carpenter Publishing.

Scott, A. 2001. Capitalism, cities, and the production of symbolic forms. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 26(1): 11‒23.

Sekulova, F., G. Kallis, B. Rodríguez-Labajos, and F. Schneider. 2013. Degrowth: from theory to practice. Journal of Cleaner Production 38:1‒6.

Silla, C. 2017. Social generativity beyond consumer society? A Weberian perspective on the dynamic of social change, pp. 121‒135 in Social Generativity: A Relational Paradigm of Social Change, edited by M. Magatti. London: Routledge.

Slade, G. 2006. 2006. Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Soete, L. 1985. International diffusion of technology, industrial development and technological leapfrogging. World Development 13(3):409‒422.

Soper, K. 2013. Beyond consumerism: reflections on gender politics, pleasure and sustainable consumption, pp. 127‒138 in Relational Architectural Ecologies: Architecture, Nature and Subjectivity, edited by P. Rawes. London: Routledge.

Soper, K. 2017. A New Hedonism: A Post-Consumer Vision. Washington, DC: The Next System Project (https://thenextsystem.org/learn/stories/new-hedonism-post-consumerism-vision).

Speth, J. and K. Courrier, Eds. 2021. The New Systems Reader: Alternatives to a Failed Economy. London: Routledge.

Spring, J. 2003. Educating the Consumer-Citizen: A History of the Marriage of Schools, Advertising, and Media. London: Routledge.

Srnicek, N. and A. Williams. 2005. Inventing the Future: Post-capitalism and a World without Work. London: Verso.

Standing, G. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. New York: Bloomsbury.

Steffen, W., P. Crutzen, and J. McNeil. 2007. The Anthropocene: Are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature? Ambio 36(8):614‒621.

Steinmueller, W. 2001. ICTs and the possibilities for leapfrogging by developing countries. International Labour Review 140(2):193‒210.

Stiglitz, J. 2008. Toward a general theory of consumerism: reflections on Keynes’s economic possibilities for our grandchildren, pp. 41‒85 in Revisiting Keynes: Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren, edited by L. Pecchi and G. Piga. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stiglitz, J., A. Sen, and J.-P. Fitoussi. 2010. Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up. New York: New Press.

Stockhammer, E., H. Hochreiter, B. Obermayr, and K. Steiner. 1997. The Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) as an alternative to GDP in measuring economic welfare: the results of the Austrian (revised) ISEW calculation 1955‒1992. Ecological Economics 21(1):19‒34.

Suzuki, T. 2013. Low Fertility and Population Aging in Japan and Eastern Asia. Berlin: Springer.

Thomas, J. and J. Evans. There’s more to life than GDP but how can we measure it? Economic and Labour Market Review 4(9):29‒36.

Toffler, A. 1980. The Third Wave. New York: Morrow.

Trebeck, K. and J. Williams. 2019. The Economics of Arrival: Ideas for a Grown Up Economy. Bristol: Policy Press.

Trentmann. F. 2004. Beyond consumerism: new historical perspectives on consumption. Journal of Contemporary History 39(3):373‒401+456‒457.

Vänska, A. 2018. How to do humans with fashion: towards a posthuman critique of fashion. International Journal of Fashion Studies 5(1):15‒31.

Varey, R. and D. McKie 2010. Staging consciousness: marketing 3.0, post-consumerism and future pathways. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 9(4):321‒334.

Walker S. 2012. Truman, reconversion and the emergence of the post-World War II consumer society, pp. 189‒209 in A Companion to Harry S. Truman, edited by D. Margolies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Wallace-Wells, D. 2019. The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming. New York: Tim Duggan Books.

Welch, D. and D. Southerton. 2019. After Paris: transitions for sustainable consumption. Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 15(1):31‒44.

Wells, P., W. Abouarghoub, S. Pettit, and A. Beresford. 2020. A socio-technical transitions perspective for assessing future sustainability following the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 16(1):29‒36.

Notes

[*] The author is Professor of Sustainability Studies and Chair of the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the New Jersey Institute of Technology.

[1] It merits noting that interest in post-consumerism tends to overlap with a number of other contemporary concepts involving the end of economic growth (post-growth, degrowth, and beyond growth), the winding down of capitalism, and the emergence of alternative conceptions of both prosperity and well-being. See Speth and Courrier (2021) for a useful synthesis of this complex and extensive literature. Also relevant here is research carried out over many years by Ronald Inglehart (1977) on “post-materialism” and more recent work by Amitai Etzioni (2004) on the “post-affluent society.”

[2] It is difficult to overestimate the extent to which Rostow’s conception has shaped thinking about the rocess of modernization over more than a half century (see, for example, Gilman 2004). It also merits notating that related conceptions such as the Kuznets Curve (and the Environmental Kuznets Curve) share many of the same tenets.

[3] This apparent termination, of course, brings to mind the famous and ferocious debate over Francis Fukuyama’s (1992) post-Cold War contention about the “end of history.”

[4] In addition to rising incomes, favorable consumer-finance arrangements (especially for home mortgages), ample supplies of consumer goods, and public investment in infrastructure it is important to acknowledge the role of industrial designers in facilitating the manufacture of products purposefully intended to prematurely breakdown and become obsolescent. The success of this business model was further abetted by an associated strategy whereby goods were (and continue to be) designed to need replacement because they are no longer fashionable. For detailed discussion of this issue, see Slade (2006).

[5] Popular expressions of moves away from consumerism include minimalism, small-scale living, zero waste, car-free lifestyles, shopping avoidance, plastic-free living, capsule wardrobes, meat-free diets, slow food and travel, and overcoming fast fashion (see Mackinnon 2021 for a useful overview).

[6] According to the World Bank, the five countries with the fastest growing economies over the five-year span 2013‒2018 were Ethiopia (9.4%), Ireland (8.6%), Ivory Coast (8.3%), Djibouti (7.7%), and Turkmenistan (7.6%).

[7] The literature on sustainable consumption governance provides a useful point of departure. See, for example, Fuchs and Lorek 2005; O’Rourke and Lollo (2015); Keller et al (2016); and Bengtsson et al (2018).